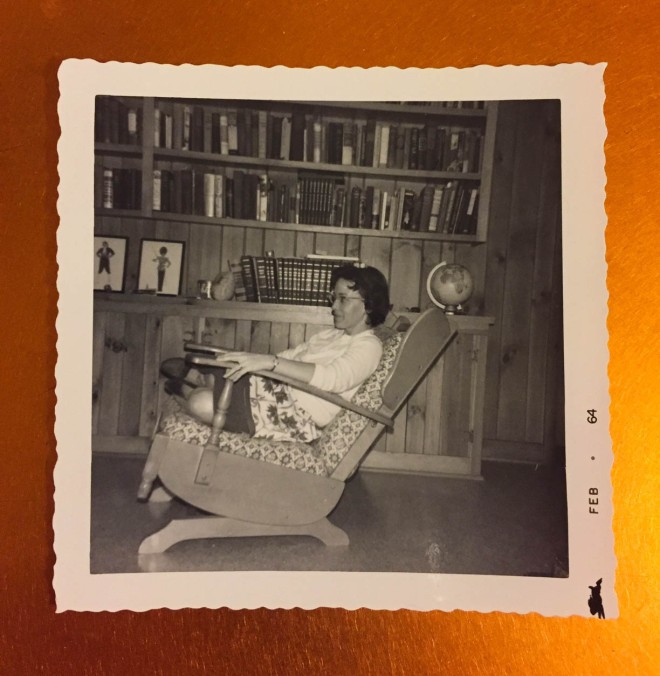

It’s been twenty-five years since my mom died. Of course I always wished I had been able to compare notes on motherhood with her (she died just weeks after my firstborn came into the world). But now what strikes me is how much I’d like to be able to talk with her about roles. About how they define you and sometimes trap you, and how you must grow past them. And why that seems so hard!

I want to know how she grew past her roles of wife and daily-mom and daughter, all in a few short years. How dizzying that must have been. I wouldn’t know, because for the most part, she didn’t tell me. Always said she was “fine,” and diverted conversation back to me, and my life. And then, suddenly, she was sick. I’ve learned not to wait on having conversations with people I care about. Or at least, I’d like to say I try to do that. I don’t always succeed. It can hurt, for one thing, and what is more human than avoiding pain? Plus I still get trapped in roles.

(And where exactly does a role end and a boundary begin, anyway? Life is so tricky.)

I’m no one’s daughter, no one’s daily-mom, no one’s wife, no one’s most-beloved. I’m just: me. Of course I still play roles—writing coach, yoga teacher, design consultant—but those roles are not cemented to relationships with specific and dear people. They are more like the roles in a play, I suppose.

A couple weeks ago, I saw a live-theater performance of the Hunchback of Notre Dame in Indianapolis, and spent the night afterwards with extended (and very dear) family. The next morning was unseasonably cool. I snuggled up on their deck and thought about the play. The day was bright with birdsong and the chatter of neighbor children. I couldn’t make out what the children were saying, exactly, but it was clear as the blue sky above that they were working out the rules of a game.

YOU will be THIS, I will be THAT.

We don our costumes early in life. Even after we grow into adults, we are, inside, run by the rules of childhood. By the labels we and others stamp on ourselves. The artistic one, the troublemaker, the bully, the little mother, the Daddy’s girl. On and on. Some of us shake them off for who we are meant to be. Others bloom into their labels, and transcend them. And I would once have denied the past ran me at all.

In the dark theater, I watched Quasimodo sing his pain and longing. Watched him be labeled at birth as monster. I think we are all “half-formed,” and destined to stay that way, unless we unearth the past and question it a little. I was the baby, the cry baby, the gullible one, the artist, the poet, the one you could trick and tease and scare easily. The one who would finally, inevitably, cry. And be told, again and again, that my tears were wrong, I was wrong, I was “too sensitive.” I learned it better not to ask for understanding; that I was making something out of nothing. I could not be trusted, and so I did not trust myself, or what I felt or even reality. It was all my artist’s imagination, my poet’s drama. Better not to cry, or, if I did cry, better not to say why. I was the unstable one, the emotional one. My mother, at her wit’s end, used to threaten, “I’m gonna give you to the trash man, if you don’t hush up.”

Now, my mother was not a monster. No, she was flesh and blood and bone and beautiful. She folded me in hugs I still feel. She was human, and struggling. I love her with all my heart. Still, she could not handle my tears, which, looking back, I think may have mainly, early on, belonged to HER, tears she could not cry lest she never stop. Mothers of four have no time to cry.

I can see her, hands on hips, pointing out the window at the trash truck, I remember her saying it—and not just once—forgetting or not caring (I think forgetting) that a little girl who still believes in Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny would never question that the trash men could take her away. I was terrified that the dark men with menacing white smiles and sooty coveralls were indeed going to lift me up like I was a clangy garbage can and roar me away in that smelly loud truck, and I’d never see my Mama again.

And so crying began to terrify me. But tears bubbled and burst out periodically. (Still do). It’s how I’m made.

Recently I had a revelation. A friend was laughing about how she thought of crying as an “emotional enema,” because she always felt so much better once all the tears came out; she felt clean and light, ready to face life again. Until the next time. Sometimes, she said, you just need a good cry. But right then it stuck me.

Crying always—with a few notable exceptions—made me feel worse. The tears bring up shame, brackish and foul, from the dark channels of early childhood. From roles I am still acting out, unconsciously?

The half-formed girl—Quasimodo girl—keeper of secrets in the attic, sleeping terrified clutching a crucifix, the voiceless one, the broken one, the trash-can girl—all my past roles lurked in the recesses of my grown self. They burrowed in deep, and curled hidden inside me for decades, only coming out at the most stressful times, sleeping and waking restlessly, pulling my strings.

On a sunny morning in Indiana, thinking about the past, memories of marriage and motherhood surged in this place of some of the best days of both those roles. Stretched out with my journal, watching the bees buzz in their hives, I felt a new me emerging, ready to really listen at last to all the hushed-up stories of trash girl’s pain, ready to watch it flame up and burn off and billow like the charcoal smoke rising up from the barbecue.

For this moment on this deck in this place, I felt at home with myself. Home is now, I thought. That is the feeling. Of being home in your body. I learned that term from a friend who held me while the hardest pieces of my childhood surfaced, jaggy, tearing me open. Held safe, I learned I could cry and feel better, instead of worse.

Now I am learning to do that alone, as I sort and grow. I’m learning to cry and sometimes actually feel better, lighter, clearer.

Quasimodo no more, maybe?

“What is ‘whole’ in Latin,” I asked my brother-in-law, who had come out to put brisket on the barbecue.

“Plenus?” he ventured.

Plenusmodo. Full-formed. Whole.

Mom knew Latin. I wish I could call Mom now and talk. About the roles she was saddled with by her childhood, about the things she locked away. About why she hid her tears and pain and struggles. Maybe we could let go of our roles, drop our masks, and just listen to each other? That’s all anyone really wants, I think.

To be seen beyond their roles in life. To be held, and heard, and loved for who they are, at the beating heart of their being.

A wonderful, poignant reflection, Elaine. How strange that we both wrote about motherhood in our blogs, on the same day… xxx

Yes, that is quite a coincidence, Angela.

I read your piece. SO GOOD. Beyond good. It has me thinking!

I love your writing style – deeply evocative. Glad we follow each other’s work! xxx

Ha! I agree with Angela above. I found it funny that you wrote about growth when I’ve just posted about it 😉

Beautiful, as always, and thoughtful and though provoking.

I can relate to so much. Not the garbage-man thing, my parents’ saying was more aong the lines of “Come here and I’ll give you something to cry about”. Not much better. So I too learnt to hide who I was, what I felt and so on.

Opening up now is like fearing to open Pandora’s box. What if I’m not ready for it?

What if I can’t take it, don’t have enough strength to fight those demons?

But then I try to remember that there is this one last little being inside the box. Hope.

Sending you lots of love Elaine. Thank you.

Thank you, Dawn. I checked out your post—it’s great. I love that video about the lobster, and your insightful reflections on growth. It IS so uncomfortable at times. But reading your post makes me feel like being uncomfortable isn’t so wrong. I think it is our culture that makes us want to avoid all pain? But pain, facing fears–that’s how we grow! Lots of love back at you, too!

The garbage can girl” — oh, my. This brought tears to my eyes, I can certainly remember feeling this insignificant. You illustrated the need for acceptance and love perfectly.

Beautifully reflective💜 thank you~

Thank you so much for commenting–I appreciate that 🙂

💜