Today is my birthday. So much has happened since I exited my mother’s womb those many years ago. The story of my birth and my mother’s labor are lost forever. All I have are a few hazy details.

Today is my birthday. So much has happened since I exited my mother’s womb those many years ago. The story of my birth and my mother’s labor are lost forever. All I have are a few hazy details.

“Oh I had twilight sleep,” my mother told me. “No memory of any of it,” she said, shaking her head each time she mentioned it, as if trying, again, to summon the experience that her body had, to shake it out somehow. “They told me I said really awful things,” she confided once. “The drugs make you crazy.” She also said it was good thing, of course. She’d felt the pain of childbirth before; I’m not sure how many of her births were “twilight” but I’m pretty sure at least one of her preceding birth experiences had happened too fast for many interventions. Maybe she really chose twilight sleep, willingly. I don’t know, and I cannot ask her. Why give birth with pain? Twilight sleep was the modern way. Like formula was modern, better than anything a woman’s breast might produce. I can see how she would choose that, or maybe feel there were no other options.

I read up on twilight sleep. From the distance of the years (it was abandoned in the late 60s/early 70s) it sounds like the stuff of nightmares, like some kind of awful date-rape drug, a mixture of Morphine and Scopolamine. It erased any memory of labor and birth, but did not eliminate pain. Often women became panicked, or even psychotic, and attempted self-harm. They were routinely restrained to their beds with lambskin-lined straps, to prevent bruising as they thrashed, a common thing when the dose was wrong.

But the body remembers even when the mind forgets, and a shadow always crossed my mama’s face when she talked about my birth, about the twilight sleep.

“It was the strangest thing,” she said. She seemed to disappear as she said it. Her face misted over, like a mirror fogged.

“In twilight sleep, sensation is still present though in diminished degree; the patient feels the pains of uterine contractions, frequently she moans, draws up her legs, and in other ways shows that she is suffering, but these painful sensations are not recorded in the memory cells… if asked a question, she will answer often in a dazed and confused fashion.”1

Today, on the anniversary of my birth, I’m thinking about pain, about the necessity of feeling what you feel—emotionally and physically—in order to move toward wholeness and health. Of course, seeking pain relief is not a bad thing. But there’s the issue of agency. Who is deciding that this is the best thing? (The same people who decided midwives and unmedicated births were a menace, that’s who.) Even if it was what Mama chose, I struggle with the issue of awareness, and the idea of not having a loving advocate while in a state where you will not remember what is done to you. (Remember, husbands paced in the waiting room back then, banished). I imagine having twilight sleep presented as the only ‘sane’ option available. Of being railroaded and gas-lighted.

While my own birth-giving experiences were not without interventions, I remember them all and I consented to each one. I felt tremendous pain, which I lived through and processed. No shadows cross my face when I remember the births of my children. I’d do things differently now, given the chance, but I made my own decisions, and had my then-husband with me the whole time.

Reading about trauma taught me that what is not processed, felt and released properly becomes trapped. I think of the trauma of being split from your body as you give birth. Far from being forgotten, unprocessed trauma lies in wait. Perhaps it was the cause of my mother’s battles with depression. Perhaps it was the cause of mine, too?

Suppression of feelings is what leads to deep despair. But I’m not depressed anymore.

Now I hunger to feel what I feel, in real time. Still, I find myself retreating into old patterns of escape. Patterns so fine I cannot even see them. Perhaps they were died into the wool of me, during my twilight birth? Knitted in during childhood experiences that divided my mind from my body? Unraveling takes time.

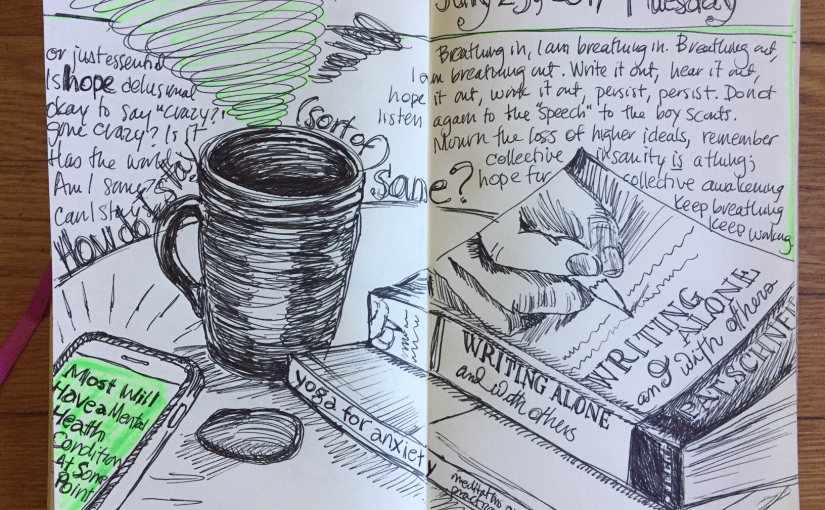

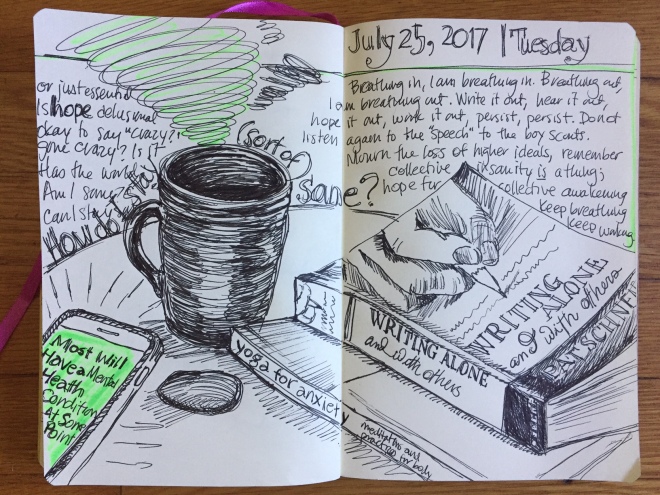

Last summer, I worked with a life-coach in her final months of training, as her test-client. The coach asked me lots of hard questions. Questions like: “and how do you feel, right now?”

I often answered in meandering, rambling ways, embroidering. She’d cut me off. “Where are you? I’ve lost you,” she’d say. “Just tell me how you feel, and where you feel it.”

Often, I didn’t know. This stunned me. Really? I didn’t know? How could I not know?

“Say you don’t know,” she coached. “Say you feel confused.”

Slowly I wake. Reams of paper, hours of walking and thousands of sun salutations later, that “where do you feel it?” question still often makes a shadow pass over my face, still frequently dazes and confuses me, still makes me shake my head as if that will help the right answer emerge from the fog of disconnection.

With another birthday comes new threads of silver hair and some bit of wisdom. I see one thing, anyway: the heart of anxiety, or my anxiety, anyway, is avoidance of feeling what I am feeling.

Or maybe: the heart of anxiety is not feeling safe in your own body.

Or maybe: the heart of anxiety is being told how to feel, to having your lived experiences denied.

Or maybe: the heart of anxiety is feeling your body is not yours to control. To have men in power who want to take away your birth control, free your rapist/harasser (if you dare to speak up at all). On a day when we have an overt misogynist in the White House and many, many other such men leadership positions, when social media is filled with #metoo hashtags denoting individuals who have been sexually assaulted or harassed, I think of the assault of not remembering the day you gave birth. Of the men that decided that was a good idea, and the women who really didn’t get a lot of choice about their birth experiences, as men made those decisions for them.

“Even if I had been asked what I wanted during childbirth,” one woman who was given twilight sleep shared, “I wouldn’t have known what to say.”2

I think of the islands of memory that were considered a ‘side effect’ of twilight sleep. Of the women I read about, laboring alone for hours in a drugged haze, feeling the pain with their bodies, who afterwards could only recall being shouted at to be quiet. Of women with eyes bandaged shut, ears stopped up, so as not to have ‘sensory memories’ to latch onto. Of the fear their bodies surely remembered, while their mental memories were magic-erased by scopolamine, a drug made from deadly nightshade. I think of the breach of trust inherent in this treatment. Birth? Oh, who’d want to remember THAT? I read about a woman, surely not the only one—who didn’t believe the baby given to her was her own, and subsequently had no attachment to her baby. I read of children born as perhaps I was, struggling to breathe (a side effect of twilight sleep), whisked away from their mothers for hours because the mothers were under the influence of dangerous drugs that made their behavior unstable, and robbed them of memories of their own experiences. Of the fathers who were also robbed of the experience of being there during birth. Of the way misogyny wounds women, and also men.

I think of my mother’s obstetrician, the same one who told her twilight sleep was the way to go, the man who weighed her at each visit, insisting she keep her weight gain under 25 pounds, and berated her when she gained too much. Because he was watching out for her, so she could “regain her figure.”

That’s a whole other layer of #metoo.

How am I feeling? Grateful for my mother’s incredible strength. Wistful that I can’t ask her more questions about how she felt. Angry at the continued denial of cultural misogyny by so many. Happy for another year of feeling what I feel, and saying what’s on my mind, what’s in my heart—or doing my best to learn how, anyway.

Better late than never.

1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2066377/?page=3

2 From “A reclamation of childbirth” by Barbara L. Behrmann, PhD

You’ve got to stay sane however you can.

You’ve got to stay sane however you can.